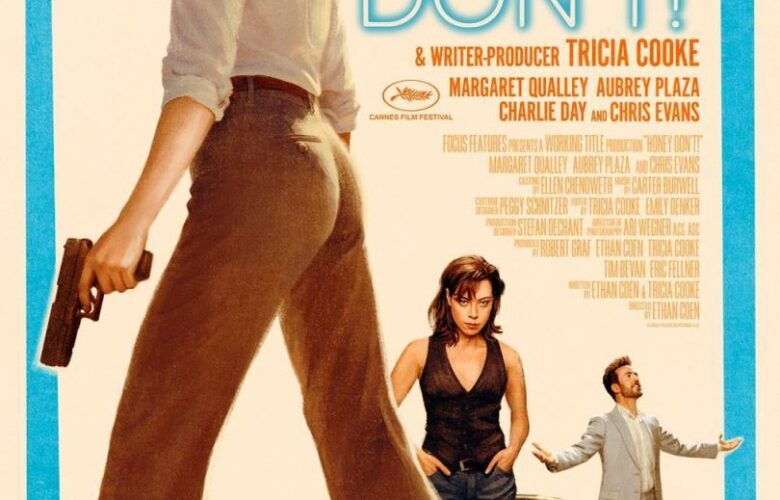

Ethan Coen’s Honey Don’t! (2025), co-written with Tricia Cooke, enters a cinematic landscape already saturated with reimaginings of film noir. Yet unlike earlier Coen brothers’ engagements with the genre (Blood Simple [1984], The Man Who Wasn’t There [2001]), Honey Don’t! rejects the slow burn of paranoia and fatalism for something deliberately gaudy, irreverent, and sexualized. Situated within the lineage of neo-noir, the film both honors and destabilizes the genre’s conventions. It does so most provocatively by reframing noir’s traditionally heterosexual, male-centered worldview through a queer, female-driven lens.

Genre Conventions and Their Distortions

Classic film noir, emerging in the 1940s and 1950s, is characterized by chiaroscuro lighting, hard-boiled detectives, fatalistic plotting, and the figure of the femme fatale—seductive, dangerous, and ultimately destructive to men. Neo-noir, particularly post-1970s, has sought to adapt these tropes to contemporary sensibilities, often heightening violence, sexuality, or narrative fragmentation (Chinatown, Body Heat, L.A. Confidential).

Honey Don’t! adopts the trappings of noir—a central mystery, shady dealings, a protagonist entangled in crime—but fractures them through stylistic excess. Bakersfield is not a city of shadows but of neon and candy-colored artificiality. The femme fatale archetype is displaced: Margaret Qualley’s Honey is not a manipulative seductress but an agent of chaos, whose sexuality is not weaponized against men but embraced as liberatory, often directed toward women.

In this sense, Coen and Cooke dismantle noir’s heteronormative scaffolding. Rather than depicting desire as a destructive force (as in Double Indemnity), Honey Don’t! treats it as playful, even joyous—though sometimes gratuitously so. Yet this inversion also creates tonal instability: by pushing noir into camp excess, the film sacrifices the genre’s usual tension and dread, leaving some critics to dismiss it as hollow parody.

Comparison with Coen Brothers’ Oeuvre

To situate Honey Don’t! in the broader Coen corpus is instructive. Ethan and Joel Coen have long been fascinated by genre deconstruction. The Big Lebowski (1998) riffed on Raymond Chandler-esque detective noir while satirizing the futility of searching for coherence in a fragmented world. No Country for Old Men (2007) stripped noir of humor altogether, presenting violence as implacable fate.

Honey Don’t!, by contrast, feels less rigorous than these earlier works. It leans into B-movie trash aesthetics and refuses the existential gravitas that often grounds Coen absurdism. Where Lebowski found profundity in absurd slackerdom, Honey Don’t! delights in absurd horniness without offering the same reflective payoff. This divergence may stem from its creative genesis: rather than a fraternal collaboration, it is an Ethan Coen/Tricia Cooke passion project, less concerned with perfection than with indulgence. As such, it might be better understood as a queer counterpoint to the Coens’ shared canon, more anarchic but also less disciplined.

Queer Subversion or Queer Exploitation?

Central to academic debates around Honey Don’t! will be its treatment of queerness. On one level, the film boldly asserts queer female desire in a genre historically built on heterosexual male fantasy. Honey’s liaisons are not tragic but exuberant, situating queerness not as noir’s destructive femme fatale trope but as generative of freedom. This could be read as a radical reconfiguration of genre, aligning the film with queer theory’s interest in destabilizing heteronormative structures (Butler, Sedgwick).

On another level, however, critics argue the film instrumentalizes queerness as spectacle. Its explicit sexual imagery can feel more like provocation than nuanced representation, what some call a “queer veneer” overlaying otherwise conventional noir pastiche. This ambivalence is reflected in the polarized critical reception: some celebrate its boldness, others deride it as exploitative.

Cult Potential and the Politics of Trash

In assessing Honey Don’t!, it may be useful to borrow from film theorist Jeffrey Sconce’s notion of “paracinema,” which valorizes films dismissed as trashy, excessive, or incoherent. By reveling in gore, camp, and gratuitous sexuality, Coen and Cooke position Honey Don’t! as a paracinematic artifact—one that embraces “bad taste” as a mode of cultural rebellion. Its garish artificiality recalls John Waters more than classic noir, suggesting a lineage of queer cinema that thrives on provocation.

This paracinematic reading helps explain why the film resonates with some audiences as liberatory while alienating others as empty. Its cult potential may rest precisely in this excess: a refusal to conform to coherence, subtlety, or moral seriousness. Whether this is a strength or weakness depends largely on the interpretive framework one brings—high-art critique or lowbrow camp appreciation.

Conclusion

Honey Don’t! occupies an unstable but intriguing space in contemporary cinema. As a neo-noir, it destabilizes genre conventions, queering and campifying a form once steeped in patriarchal fatalism. As a Coen-adjacent project, it both continues and diverges from the brothers’ tradition of genre play, replacing intellectual rigor with anarchic indulgence. And as a queer cinematic artifact, it raises the question of whether bold representation risks slipping into exploitative spectacle.

Ultimately, Honey Don’t! may not succeed as coherent storytelling, but its cultural value lies in its provocation. It insists that noir—a genre obsessed with darkness, doom, and repression—can be reframed as colorful, horny, and chaotic. For some, this is exhilarating; for others, exhausting. Either way, it guarantees the film a place in discussions of how cinema continues to wrestle with genre, desire, and identity in the 21st century.